A friend of mine died last week. His death, which surprised all of us, led me to think a lot more about my two friends living with pancreatic cancer. Both were diagnosed within months of each other about three years ago and both underwent Whipple surgery and chemotherapy, and both go in for a battery of tests every six months. I’ve been supportive of my two friends living with cancer, no doubt, but it was after the death of my other friend last week I realized I never fully considered what it meant to live with cancer, and to live with one that’s under active surveillance and can make itself known any day. I realized I hadn’t imagined what it must feel like to wake up everyday and wonder whether there will be some sign – a cough, a moment of double vision, an ache in the abdomen – that could mean the cancer’s back and spreading, or mean nothing at all. What is it like to live with such a sense of uncertainty – of radical contingency – for the rest of one’s life?

This train of thought led me to consider how a clinician working with patients who’ve survived all manner of calamities, traumas, and sorrows should comport themselves, to approach patients with empathy and compassion to the extent possible.

I’ve written about compassion fatigue and burnout on several occasions. Today, I focus on how to maintain (or even increase) one’s empathy and compassion towards patients without this leading to clinician burn-out. I want to share with you how I think about and maintain sustainable empathy and compassion.

Empathy comes in three types: intellectual, emotional, and compassionate. Intellectual empathy refers to understanding on a cognitive level what another person is feeling and thinking. It extends to anticipating what challenges they may face in their lives and their possible reactions to those evolving challenges. The key task is taking the perspective of another person. Emotional empathy refers to experiencing within one’s self the feelings and physical sensations of another person’s emotional state. The key task involves imagining a similar scenario from your own life or imagining yourself living – not just pretending to live – what the patient lives through and experiencing directly the pain, fear, sadness, and anger such a situation engenders. And compassionate empathy refers to feeling moved to help in some way the person in distress. The key tasks are having the motivation and skill to act effectively.

All three types of empathy are important to being an effective clinician. Emotional empathy is perhaps central: it forms the foundation that allows effective perspective-taking. Without experiencing at least some anguish for oneself, it is hard to know what emotions and practical challenges may be at play for the patient. Also, the emotional aspect provides the motivation and suggests the right actions to take.

My Method for Sustainable Empathy and Compassion

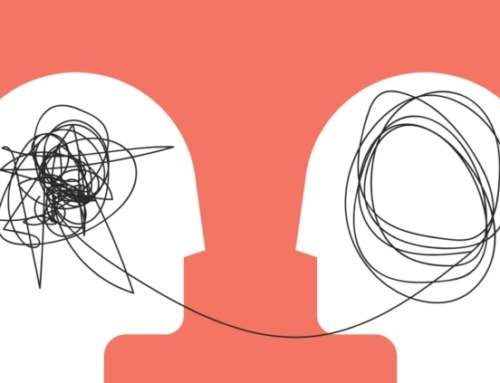

Now, here’s where my method kicks in: I do not seek to experience full emotional empathy every time a patient shares with me a terrible, traumatic, or sorrowful situation. In fact, I often monitor and modulate my level of emotional empathy, and allow myself to feel the pain and uncertainty only to the degree it allows me to understand the pertinent issues, that is, to competently develop intellectual empathy and compassionate action. I don’t need to feel pain to be motivated to help. I see that as core to what I do – it’s my job. I don’t need to feel pain as a method of communicating to the patient that I care. I don’t believe that a person in pain needs or wants another person to experience the same pain they’re experiencing. Rather, I believe a patient needs someone who understands, who cares, and who acts with competence. In fact, if a patient were to notice that their clinician is too much in pain, this realization could be frightening. After all, someone in the room needs to be strong, decisive, emotionally controlled, and able to act quickly and competently. And this someone needs to be the clinician which then allows the patient to experience, explore, express their emotional distress in a safe environment.

For me, the first step to empathy and compassion is showing curiosity. As I wrote at the start, the death of one friend made me more curious about how my two friends living with cancer were handling their precarious health. I was moved to more fully consider their perspective. Thus, the next step in empathy involves active listening, exploration, and the confidence to ask the hard questions. If I were working with a patient living with cancer, I would ask them how it felt living with such uncertainty. Their answer would lead to further questions and moments of silence and contemplation. I would be listening for feelings of grief, anger, sadness, and fear. I would tell them that their feelings were normal and expected and could help them get in touch with what is truly important in such a challenging time of life. I’m sure at the end the patient would feel understood, relieved, and feeling less alone. I would have done my job, without unduly draining myself emotionally.

Similarly, with patients living with the aftermath of trauma: I have tried hard to feel the pain of trauma and summoned up my own experiences of hurt and betrayal in service of helping me be a better perspective-taker. I’ve done this in the past, but I don’t try to live the pain with each patient anew now. Rather I ask questions, empathize, normalize, and say things that convey I understand the nature of both core PTSD symptoms and all the fellow travelers, such as the sense of grief engendered by someone stealing that patient’s sense of innocence, carefree living, expectation of healthy relationships; and leaving them with a sense of betrayal, chronic vulnerability, and fragility. I often say something like, “You can’t unexperience what you’ve experienced, and you can’t unsee what you’ve seen. That’s what was taken from you. Is it unexpected that you’re left with anger and sadness and a sense of vulnerability? With time you will heal, but you will be different than if this never happened to you.”

To summarize: I believe I can reach across the distance between two people, in this case, between clinician and patient, by demonstrating my desire to understand, to share what I have understood, to show continued curiosity to better understand, to say what needs to be said, to keep emotionally even-keeled, to show commitment to continue on the sometimes long journey towards healing, and to show the courage to continue even in the face of death’s inevitability.

Your Own Corner of the World

An additional danger for people who are by nature compassionate is to feel overwhelmed by the world’s needs and deep wells of suffering experienced by the creatures of this world. You have two choices: do nothing or do what you can. It’s sometimes hard to accept one’s limits and even harder to say “No” when it needs to be said. I like to offer the reminder: no one will ever say “No” for you. No one will say, “You’ve done enough, now go home and rest.” You must be realistic about your limits and live within sustainable boundaries. And you must do so even though you know full well that it will never be enough.

Today’s Quotes

“When people talk, listen completely. Most people never listen.”

Ernest Hemingway“Resolve to be tender with the young, compassionate with the aged, sympathetic with the striving, and tolerant of the weak and the wrong. Sometime in life you will have been all of these.”

George Washington Carver“It’s the hardest thing in the world to go on being aware of someone else’s pain.”

Pat Barker“Empathy requires knowing you know nothing. Empathy means acknowledging a horizon of context that extends perpetually beyond what you can see.”

Leslie Jamison“Can I see another’s woe,

And not be in sorrow too.

Can I see another’s grief,

And not seek for kind relief.”

William Blake

Leave A Comment